Security researchers have been warning for years that the expanding IoT attack surface isn’t driven by flagship smartphones or laptops, but by the secondary devices permanently paired to them. Baby monitors, smart TVs with cameras, streaming players, connected appliances—and now wireless headphones and earbuds—operate as trusted endpoints with persistent Bluetooth access and minimal user visibility. The latest disclosure brings that risk into sharp focus. Multiple critical vulnerabilities have been identified in Bluetooth System-on-Chips from Airoha Technology, a major silicon supplier whose SoCs are embedded in headphones and earbuds from Sony, Bose, JBL, Marshall, and Jabra.

These chips do far more than maintain a Bluetooth connection. They run the software that controls how your headphones pair with your phone, manage audio processing, handle microphones for calls and voice assistants, and maintain the trusted relationship between the headset and your smartphone. In practical terms, the chip inside your headphones decides what the device can hear, what it can transmit, and which devices it trusts.

When security flaws are found at this level, attackers don’t need to break into your phone directly—they can exploit the headphones as a weak link, using them as a doorway to listen in or interact with the connected phone without the user ever realizing it.

Verified vulnerable devices include several widely owned, mainstream models, not just niche products. Most notably, multiple Sony WH and WF series headphones are affected—including the extremely popular WH-1000XM5 and WF-1000XM5, two of the best-selling noise-canceling headphones and earbuds on the market. Also on the list are Bose QuietComfort Earbuds, a staple for frequent travelers, along with JBL Live Buds 3, which sell in very high volumes through big-box and online retailers.

Marshall models such as the MAJOR V and MINOR IV are affected as well, alongside additional products from Beyerdynamic, Jabra, and Teufel. In other words, this isn’t an edge-case problem limited to obscure gear—some of the most commonly used wireless headphones and earbuds are squarely in scope.

Here’s what you need to know about how so-called headphone jacking attacks actually work, why these newly disclosed vulnerabilities matter in the real world, and—most importantly—what practical steps you should take right now to reduce your risk. This isn’t about panic or paranoia; it’s about understanding that the devices sitting on your head are no longer dumb accessories, and treating them with the same level of caution you already (hopefully) apply to the phone in your pocket.

How the RACE Protocol Turns Bluetooth Headphones Into an Attack Vector

Researchers at ERNW, a European cybersecurity consultancy known for dissecting wireless and embedded systems, uncovered a serious design flaw affecting a wide range of Bluetooth audio products built on chips from Airoha Technology. At the center of the issue is an internal protocol called RACE—short for Remote Access Control Engine—that was never intended to be exposed outside the factory or service bench. This is precisely the kind of vulnerability ERNW is known for finding: problems that slip through certification and testing, only to surface after products are already deployed at massive scale.

RACE exists to make life easier for manufacturers. It’s used for diagnostics, servicing, and firmware updates during production and repair. On affected devices, however, ERNW found that RACE is accessible over multiple interfaces, including Bluetooth Low Energy, Bluetooth Classic, and USB connections, without proper authentication. In plain terms, the same low-level control tools engineers use to build and fix headphones can be reached wirelessly by someone nearby. Once accessed, RACE allows reading from and writing to device memory—both flash storage and active RAM—effectively turning a pair of headphones or earbuds into a small, fully controllable computer rather than a passive audio accessory.

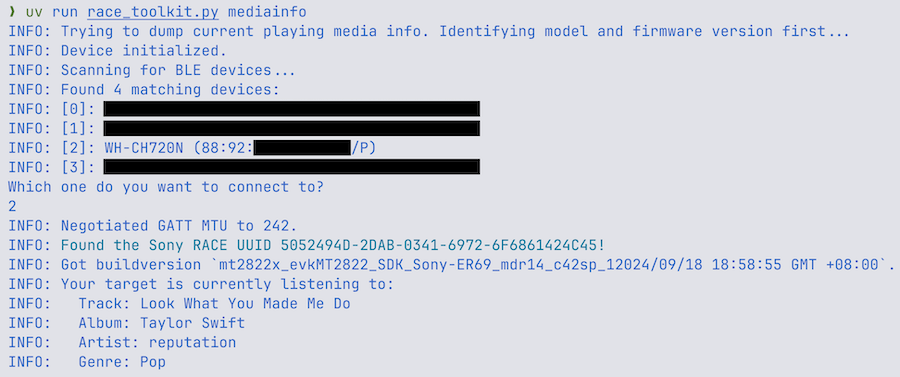

In June 2025, ERNW researchers Dennis Heinze and Frieder Steinmetz disclosed multiple critical Bluetooth vulnerabilities affecting dozens of popular wireless audio products. The exposure spanned headphones, true-wireless earbuds, microphones, and speakers using Airoha Bluetooth Systems-on-Chip. The most troubling aspect was how little effort an attacker needed to get started. As Heinze stated at the time, “Any vulnerable device can be compromised if the attacker is in Bluetooth range. That is the only precondition.”

If successfully exploited, the implications go well beyond a theoretical security bug. Attackers could read media data from audio devices, intercept microphone recordings, impersonate headphones to issue commands to a paired smartphone, and quietly eavesdrop on conversations. That combination pushes these vulnerabilities out of nuisance territory and into the realm of real-world risk—especially given how casually most people still treat the security of the devices sitting on their heads every day.

Airoha subsequently released an updated software development kit to hardware vendors to mitigate CVE-2025-20700, CVE-2025-20701, and CVE-2025-20702, and firmware updates have slowly begun to appear. Since then, Heinze and Steinmetz have published an updated technical report detailing the attack methodology and released a dedicated tool that allows researchers—and consumers—to test whether specific devices remain vulnerable. Their work, also covered by Forbes, underscores that this is not a theoretical exercise but a live ecosystem problem that depends heavily on vendor follow-through.

That’s where the warning lights really start flashing. Users of affected products must update firmware to be protected—but in many cases, updates either don’t exist or haven’t been clearly documented.

Partial List of Impacted Devices

- Beyerdynamic Amiron 300

- Bose QuietComfort Earbuds

- EarisMax Bluetooth Auracast Sender

- Jabra Elite 8 Active

- JBL Endurance Race 2

- JBL Live Buds 3

- JLab Epic Air Sport ANC

- Marshall ACTON III

- Marshall MAJOR V

- Marshall MINOR IV

- Marshall MOTIF II

- Marshall STANMORE III

- Marshall WOBURN III

- MoerLabs EchoBeatz

- Sony Link Buds S

- Sony ULT Wear

- Sony WF-1000XM3

- Sony WF-1000XM4

- Sony WF-1000XM5

- Sony WF-C500

- Sony WF-C510-GFP

- Sony WH-1000XM4

- Sony WH-1000XM5

- Sony WH-1000XM6

- Sony WH-CH520

- Sony WH-CH720N

- Sony WH-XB910N

- Sony WI-C100

- Teufel Tatws2

A partial list of impacted devices (listed above as of December 27, 2025) has been released, and anyone using those products should check directly with the manufacturer for firmware or security updates. The scale of the issue remains unsettled. “Due to the sheer amount of devices that are potentially still affected,” Heinze warned, “there is no proper overview over the current status of fixes.”

As Heinze confirmed, “An update might not be available, or the vendor might not have released information about whether the vulnerabilities were addressed in an update,” with only products from Beyerdynamic, Jabra, and Marshall known to have received fixes so far.

The Bottom Line

For most people, the odds of someone actively targeting their Bluetooth headphones are low—but low risk doesn’t mean zero risk, especially in a world where nearly every object around us now talks to something else. Wireless headphones aren’t just speakers anymore; they’re always-on IoT devices with microphones, memory, and persistent trust relationships with our phones. That alone changes the conversation.

Some manufacturers deserve credit for taking this seriously, others far less so, and that uneven response is part of the problem. The reality is that our growing dependence on interconnected devices makes vulnerabilities like this inevitable. Is this the cybersecurity crisis of the year? Probably not.

Don’t overthink this. If your headphones or earbuds support firmware updates, install them—now. Then take five minutes to clean house in your phone’s Bluetooth settings and remove any old or unused pairings. Wireless headphones are no longer harmless accessories; they’re networked devices with microphones and persistent access to your phone. When the fix is this easy and the downside involves your conversations and your data, rolling the dice makes no sense.

Update

Update Jan 6, 2026: Since posting our original story we have learned additional firmware fixes have been released.

Airoha released the official patches to affected partners on June 4, 2025, but doesn’t control when each company implements it.

JBL notified us: “JBL remains committed to delivering high-quality audio experiences that prioritize both performance and user safety. JBL has released OTA firmware updates for two impacted products in July, 2025, which customers can install from the JBL Headphones app.”

- JBL Live Buds 3: OTA online date – 7/8/2025, Firmware Version – 8.0.0

- JBL Endurance Race 2: OTA online date – 7/30/2025, Firmware Version – 5.4.0

Bose said, “the vulnerability was limited to our QuietComfort Earbuds, and in September we released version 1.2.1 of the Bose QCE app, which included a security fix for this issue.”

For more information: https://static.ernw.de/whitepaper/ERNW_White_Paper_74_1.0.pdf

Related Reading: